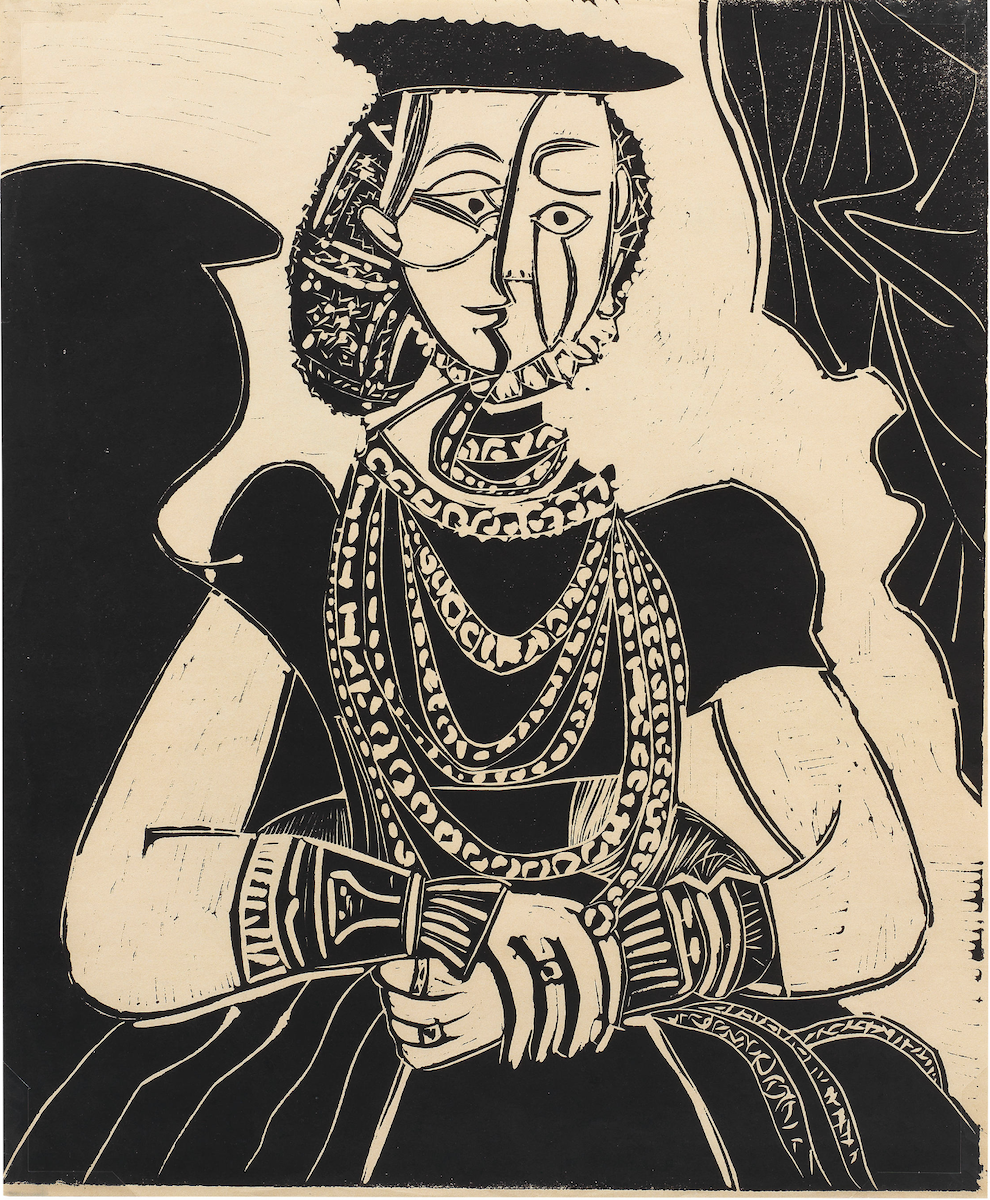

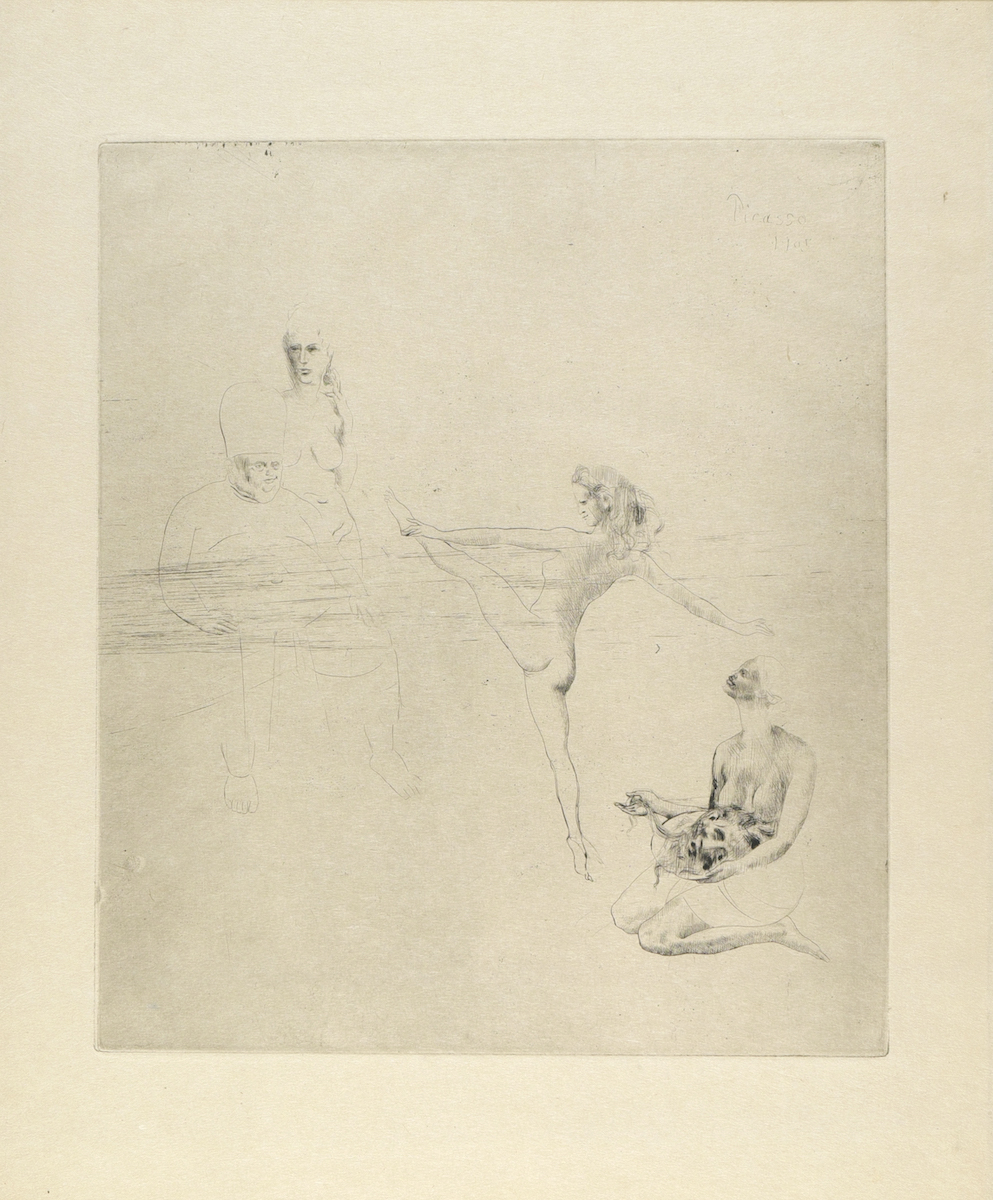

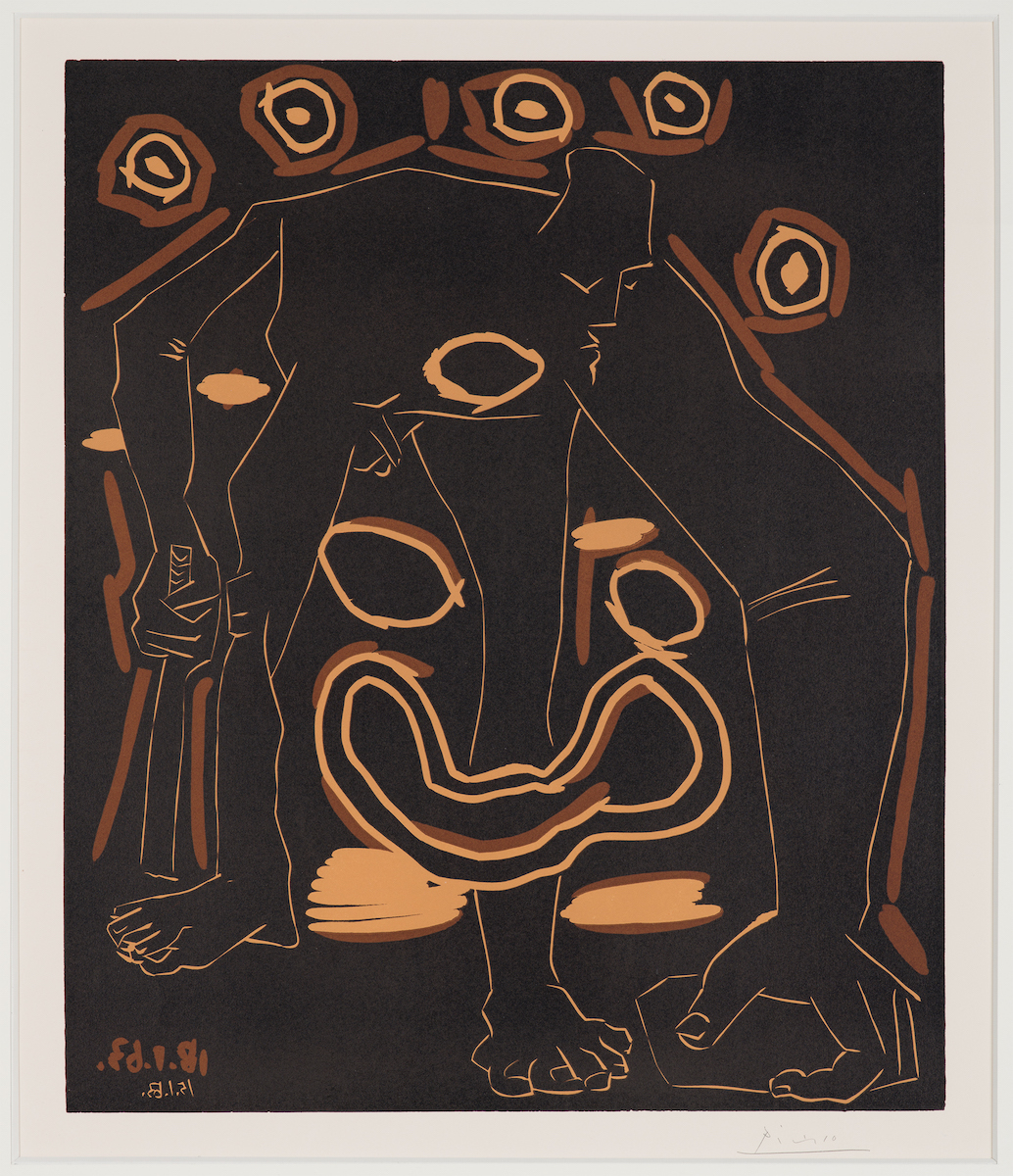

When his uncle Philippe died suddenly, Jean-François Cazeau was not yet fifty and, despite having been a merchant for seventeen years, considered himself almost a novice. ‘The quality of this profession is patience,’ says the man who, having sown his own seed since 2009, is now beginning to reap the first rewards. In his Marais gallery, Picasso is now playing elbows with Léger, while a Walking Woman by Giacometti is making its way between Masson and César. Collectors dreaming of a Renoir or a Germaine Richier bronze certainly know where to turn. Each of the pieces, arranged as if in a flat just a few steps from the Musée Picasso, has its own story, its own uniqueness, justifying its value.

‘I received a military or religious education from my uncle,’ says the Parisian gallery owner, who has retained a hint of his Béarn accent. With this renowned tutor, who himself trained with the Wildensteins, Jean-François learnt about artists and art history, of course, but also how to understand collectors. Those who put their trust in him are not the compulsive type, and eschew the ‘marketed contemporary’ of millionaire artists marketed by mega-galleries. ‘It takes thirty years to know if a work is going to hold up,’ he says, defending the timelessness of Pierre Bonnard, Georges Mathieu and Bernard Buffet.

Rather than sell off in the panic of a crisis, Jean-François Cazeau has mastered the art of stockpiling: a major Soutine, bought at the scrapyard in the 90s, then passed from fair to fair without finding a buyer, broke an auction record a little over a decade later. According to the emancipated nephew, ‘The blue chips are getting their price back before the others’, and he allows himself the occasional splurge on living artists who have the good taste to remind us of Soulages or Miro.

The ‘second market’, as it is known, delivers its own dose of adrenalin, for the dealer who holds in his hands a part of humanity’s heritage. Here, risk-taking is based on expertise in authenticity, provenance and conservation. ‘It’s also about instinct – it’s an apprenticeship,’ says Jean-François Cazeau. As for commercial sense, it is expressed through the art of conversation, fuelled by the presentation of antique objects, here a Khmer lion’s head, there a few objects over 4,000 years old. ‘Buyers, especially foreign ones, appreciate being taken down the side roads. When they come to see us, it’s also to learn what we’ve taken the trouble to find out. You’re always someone’s novice.

Portrait by Daniel Bernard